From Sketches to Early Photographs

The knowledge of geology, particularly sedimentology, has been successfully transferred and shared for hundreds of years through sketches. Just like a botanist or a zoologist, a geologist can record field data using only paper and pencil in the form of drawings (see one of the oldest published geological sketches in Figure 1). Geological maps and sketches of outcrops are the two basic elements of field data for a geologist. For a sedimentologist, a primary goal may be to show the spatial distribution and geometry of sedimentary ‘units’ (i.e., bed, member, formation, group, and supergroup).

The advent of photography could be considered a first breakthrough in the collection and sharing of outcrop data (Figure 2 shows one of the oldest photographs taken for geological purposes). Any drawing is an artistic representation of ‘reality,’ while a photograph is an almost perfect 2D representation of it. The more realistic the representation, the better anyone can observe the qualitative and quantitative characteristics of an outcrop. In summary, ideally, outcrop data should be shared exactly as if one were physically there to measure and observe the characteristics of the sedimentary rock. However, there are issues that prevent an outcrop from being represented in such a way; for example, the wide range of scales of all features, the potentially infinite amount of data that can be recorded, or the fact that some data are qualitative (e.g., color, texture determined in the field), so the instrument used to record images of the outcrop could offer a significantly different image from what our eyes and brain process. Let’s move on to recent technological innovations that have made it possible to record outcrop data across a broader range of scales and features.

Aerial Images: Airplanes and Satellites

Soon, the military realized the benefit of taking photographs of any territory from the air: the perspective and scale of viewing would provide information about enemy positions and the routes of ground vehicles. Geologists also immediately recognized the value of aerial photography for mapping. U.S. geologists pioneered this in the late 1920s[1], using aerial photographs to differentiate soil types and lithology based on shadows in black-and-white photographs. However, the real breakthrough was the deployment of satellites, which incorporate high-resolution lenses and a wide range of sensors. The major leap forward was the multispectral satellite image, which allowed for high-precision predictive mapping of large territories around the Earth. In 1972, NASA launched the first multispectral satellite with the Landsat Mission. Multispectral sensors measure electromagnetic signals in specific ranges of the solar light spectrum, making it possible to identify a variety of minerals. By 2022, the WorldView-3 satellite is at the forefront of satellite imaging. This satellite uses 16 bands positioned in the near-infrared and shortwave windows, allowing for the identification of a wider and more accurate range of minerals, as well as a spatial resolution of 1.25 to 3.7 meters for mineral analysis (Figure 3). Satellites help map geologic features on a relatively large spatial scale and identify general lithologies over broad regions, but what about the collection of outcrop data on a smaller spatial scale?

The Arrival of Drones: Democratizing Outcrop Data Collection

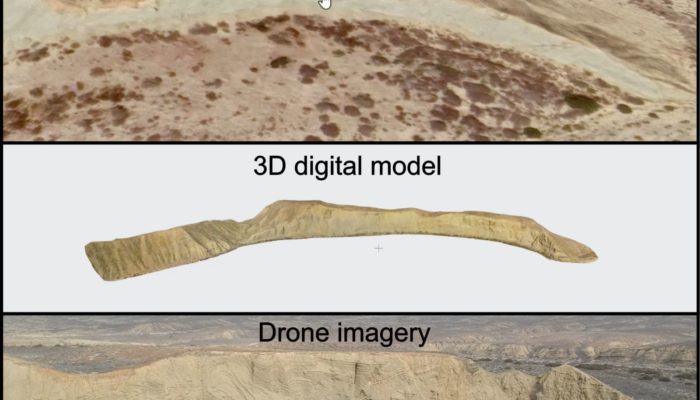

Today, it is no longer necessary to pay hundreds of euros to rent a private plane or helicopter to take photos from the air. We can buy a drone for a few hundred euros and collect photos for years (unless you crash it!). The availability of relatively inexpensive drones with good optics (i.e., camera lens) allows any geologist to collect images from any distance and angle of a given outcrop. More importantly, it enables the collection of images of outcrops that were previously inaccessible. Drones have also facilitated the operation of topographic techniques such as LIDAR and photogrammetry[3]. These techniques aim to provide high-resolution topographic models of the terrain and are now easier and cheaper to perform thanks to commercially available drones. In the case of LIDAR, it will require more investment than photogrammetry because a Lidar sensor that will be mounted on the drone must be purchased.

Virtual and Augmented Reality: The Next Advanced Experience?

Current innovations in data storage and management, along with technical advancements in hardware, point toward the development of virtual class or training tools[4]. Can these tools effectively transfer knowledge with the same quality as a live field experience? Definitely not. As an instructor of online and field courses, I have evaluated students and learners first by analyzing outcrop data from 3D models, photos, and videos created with drones, and then taken them to the field at the same outcrop. The result: they consistently show poorer observation of key sedimentary features compared to the live field visit (see an example of this problem here: Outcrop Data Comparison). Poor observation of data will inevitably lead to poorer transfer of knowledge and skills. No photo or 3D model today can match a live visit to an outcrop, but we must not forget that we could not showcase many excellent and inaccessible outcrops to other students and professionals without the help of drones. There are many advancements, but today the best way to learn geology is by combining live visits to outcrops with satellite data, drone data, and other remote sensing techniques.

[1] www.asprs.org/wp-content/uploads/pers/1947journal/dec/1947_dec_557-565.pdf

[2] https://effigis.com/en/new-era-geological-mapping-multispectral-satellites-advanced-data-processing

[3] www.propelleraero.com/blog/drone-surveying-misconceptions-lidar-vs-photogrammetry/#:~

=Lidar%20is%20a%20direct%20measurement,overlap%20and%20sufficient%20ground%20control

[4] www.earthmagazine.org/article/fieldwork-among-pixels-virtual-and-augmented-reality-diversify-geoscience-education/